Test Your Network

How much attention are you paying to one of the primary drivers of your health and happiness?

You’re about to find out.

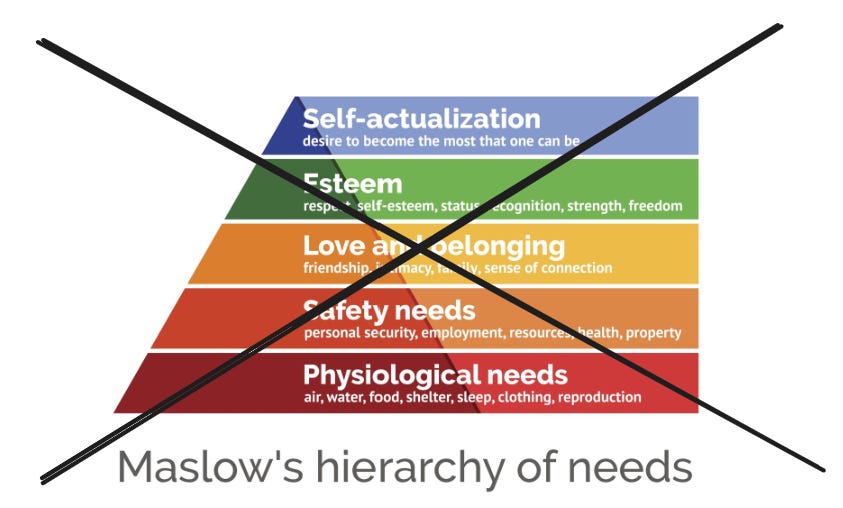

I’ve always been uncomfortable with hierarchies of development and consciousness. Talking about “higher” or “lower” consciousness just seems to be a sneaky way to reinforce isolation and ego by feeling superior to other people.1

This is because I believe we are mistaking networks for hierarchies.

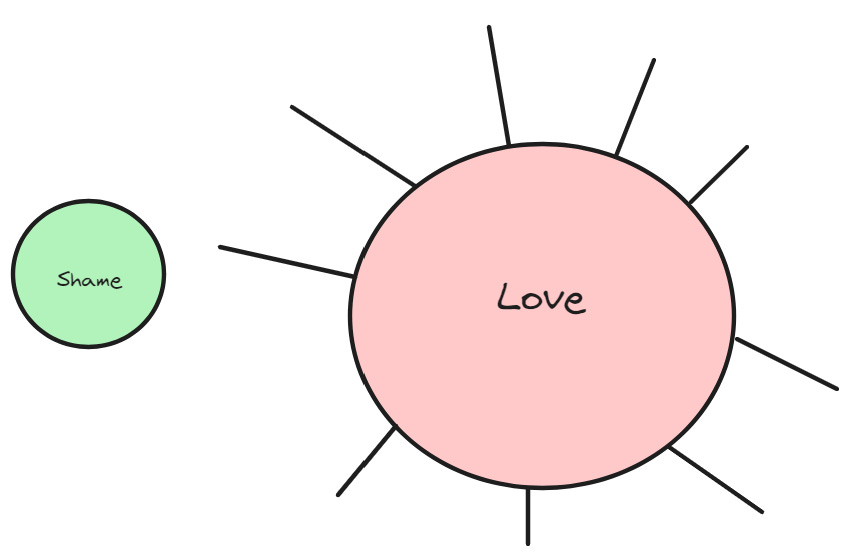

The Western capitalist ideal is the CEO alone at the apex of a corporate pyramid. And yet the happiest people I know are nodes in giant networks rather than isolated at the top of a hierarchy. This reframing means switching our perception of consciousness from higher/lower to connected/disconnected. For example, if you examine the consciousness “hierarchy” from David R. Hawkins below closely enough, you actually notice it’s a network. The lowest rung is shame: a state defined by total isolation. The highest is enlightenment, defined as being totally at one with everything.

If you reframe the hierarchy as a network, your “power” comes from the strength of your connection to other people, and the love that is able to flow through those connections.

Abraham Maslow is renowned for the most famous hierarchy in personal development, which is commonly depicted as a pyramid. Most people now know Maslow himself never used this design. In fact, there are signs he fully recognised the importance of networks and communities.

When he was 30, Maslow visited the Blackfoot Native American tribe. He estimated that 80–90% of the tribe had a quality of self-esteem that was only found in 5–10% of his own population.2 In an unpublished essay from 1966, 23 years after he published his paper on the Hierarchy of Needs, Maslow wrote:

…self-actualization is not enough. Personal salvation and what is good for the person alone cannot be really understood in isolation. The good of other people must be invoked as well as the good for oneself. It is quite clear that purely inter-psychic individualist psychology without reference to other people and social conditions is not adequate.

The paradox is that, the stronger your community support, the more freely you can pursue your unique gifts. Moreover, Maslow realized the Blackfoot simply had no conception of self-determination outside of their community. There was no individual poverty because if you lacked something essential, the tribe would give it to you. Whereas wealth was determined by how much you could give away. Our economic structure makes this so hard because if you start falling through the cracks in atomized modern society, there is often very little to catch you. I also often wonder if the current epidemic of attention disorders is being exacerbated by each of us being expected to do the work of an entire community. It certainly puts pressure on our partners; as psychologist Esther Perel puts it: “today, we turn to one person to provide what an entire village once did: a sense of grounding, meaning, and continuity.”

The point here isn’t to look backwards by romaticizing indigenous culture, it’s to make sure that learning this lesson is central to our futures.

What We Say vs What We Do

I think most of these observations are pretty intuitive so far. But there’s often a world of difference between knowing something and doing it.

Professor Marissa King is the author of the enjoyable book Social Chemistry. She has a short survey that will take you about ten minutes to complete. It reveals the structure of your personal network as well as illustrating which people are your strongest social connections. It will also classify what kind of social network type you belong to. I cannot recommend it more highly. It forces you to look very objectively at your own community structure.

The quality of your network is defined by size and time. Dunbar’s Number is the robustly-proven finding that the optimal human group size is somewhere around 150 people, but the typical network is far from evenly-distributed. Perhaps less well-known is that Dunbar believed your network scaled from an intimate circle of 5, followed by successive layers in rough multiples of three: 15 (good friends), 50 (friends), 150 (meaningful contacts), 500 (acquaintances) and 1,500 (people you can recognize). Recent research confirms that this relationship has held surprisingly constant, even now many of our friendships have been digitized.

We each average 3.5 social hours per day, so that’s 1 minute 45 seconds per friend. But it’s also not linear. Dunbar found that something like 40% of this social time is devoted to the five people in our innermost social circle, the support clique, with another 20% devoted to the ten additional people that make up the fifteen members of the support group.

King’s survey will indicate who those people are, and how much time you spend with them. It’s then up to you to work out if they are the people you would voluntarily place in that bracket…

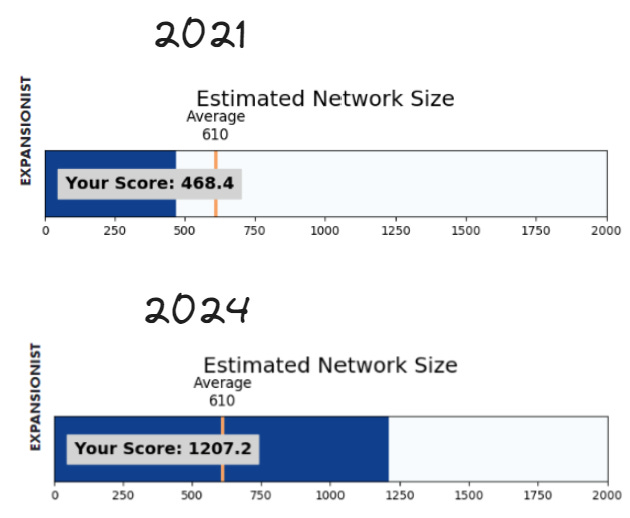

I took King’s survey in 2021 and then again before writing this article in 2024. The difference is radical: my network size has increased by 160% while still maintaining the same density and intimacy.

Why the change? While it was initially isolating, Covid lowered the barrier to meeting virtually. Now a significant number of the people in my inner circle are new friends who I initially met on Twitter and Zoom. The more authentic you are online, the more easily your vibe attracts your tribe. I try to take every meeting and reply to every message. Since founding The Leading Edge there has been another step-function increase in both quality and quantity. When you add in my two young children, the love in my life has increased beyond my wildest dreams.

When looking for community some of the requirements are obvious: loving, resilient and intimate. But in today’s individualistic world I think it’s less obvious that the benefits of a community are often determined by the degree of your commitment to it. Coach and author Brian Whetten believes that ten percent of the value you bring to a community is from what you say and do with them. Thirty percent comes from the relationship you create together. But sixty percent comes from the financial, time or resource commitment you bring to the relationship. True, subtle power scales with love, so the love you can give and receive in your personal network will be one of the primary deciders of how your life goes. Dunbar found that robust social groups correlate remarkably powerfully with everything that’s important (health, happiness and lifespan for a start). And yet they dwindle with age, especially after parenthood.

His recommendation is the same as mine: cultivate or create a community worth committing to.

1 This balanced criticism of Ken Wilber’s Integral Movement (and hierarchies of development) from Mark Manson is pretty great.

2 Really interesting article on Maslow and the Blackfoot