Adventure Capital: An Interview with Jim O'Shaughnessy

A win-win model for generational wealth

Jim O’Shaughnessy is a pioneer in the field of quantitative investing and founder of O'Shaughnessy Asset Management. Jim also recently founded OSV (O’Shaughnessy Ventures).

I believe OSV is the one of the most creative and meaningful uses of legacy wealth I’ve encountered. It seems to have benefited both Jim’s daily life and the world enormously.

A year on from launch, I interviewed him to see how his project is going [also available on YouTube here].

Tom Morgan: Ladies and gentlemen, it's Tom Morgan with Jim O'Shaughnessy. Jim is a great friend, a man I consider deeply privileged to know, but also arguably doing the most interesting thing with his time and money of anyone I know right now in the world. And so the purpose of this interview is for Jim to have a platform to explain what he's doing, why he's doing it and how it's gone.

I don't want to assume that anyone listening really has any prior knowledge of what OSV is. So Jim, if it's okay with you, I’d just like the first few minutes for you to explain what OSV is and what it spent the last year plus doing.

Jim O'Shaughnessy: Thanks for having me, Tom. So OSV is O'Shaughnessy Ventures. It is my, I guess, my next act in starting companies to do things that I'm fascinated by and interested in. I spent most of my life as an asset manager and we sold the company O'Shaughnessy Asset Management to Franklin Templeton and I launched this as my new adventure January 1st, 2023. OSV is basically a reflection of all the things that I am fascinated by and interested in. So we have different verticals.

We have a Venture Capital vertical, which really tries to hearken back to the days when they called it liberation capital or adventure capital. We're very lucky in that we don't have any LPs. So we don't have any of the problems that typically arise from an agent principle morass. We could talk about that for the rest of the podcast.

I love movies and I think that the future of movies is going to be bright, especially with the ability for very creative humans to use the new tools of artificial intelligence, to essentially be able to create things that an individual or group of individuals simply could not have done just a few short years ago. I do believe, passionately believe, that it's got to be a union of human and machine, or the so-called Centaur model, because I think that you'll see a lot of just purely AI generated stuff. And I think for the most part, it's going to be pretty much garbage. I do think, however, that very creative humans are going to be able to make incredible things with AI and the tools that it affords them. I also got tired of remake after remake after remake after remake and really wanted to see films that inspired people again, that gave them hope and or a nudge that, hey, things might not be going great for you right now, but they can go better. I think of the classic movie, Rudy, about the kid who goes to Notre Dame and as I think one of the lines goes: ‘you're five foot nothing and you weigh a buck nothing. How are you ever gonna get on the Notre Dame football team?” And it's just a very inspirational movie. And I think that there is a dearth of those right now. And so we wanna make some.

Infinite Books, same thing. We see so much hand wringing, so much doom saying. And I think that that infects the collective zeitgeist or collective unconscious. And so in our small way, we hope to publish authors that have a different perspective on what the future might hold for us.

And we also do Infinite Media. Same thing; driving that we want to be able to incubate and or collaborate with people who are looking for things to root for as opposed to against. Anybody can root. It's so easy to root against things. And so it takes a little more effort to root for them. And I want to see what we can do to help amplify that.

And we also do, and probably what we're best known for right now is the fellowships and grants that we give on an annual basis. So last year was the inaugural year of that. We gave 12 fellowships of $100,000 each. The idea for the grants and fellowships came when I was thinking about the idea that, as the world has become more and more interconnected, and as we, I hope, are building the human colossus in which we can collaborate and identify people with great ideas that previous generations just didn't have access to. Up until maybe a couple of decades ago, a genius could be born, lived, and died, and even the genius didn't know they were one. And there was no way to find them. There was no way to amplify them. There was no way really for people like me sitting here in Connecticut. I was very limited by my geography and by my networks under the old sense of the word. Well, that's not true anymore. And we now have an interconnected world in which we can find and fund geniuses all around the world. And the idea there was simply: If you can do that, you've got to do that. And so we made the fellowships and grants, we thought, fairly different in that there are literally no strings attached. You don't owe us anything if you get a fellowship from us. You can go to college or not go to college. Of course, Peter Thiel being very famous for his fellowship in which one of the requirements is that you drop out of school. And there are a bunch of others, but many of them come with significant strings attached to them. Not all. I've seen several really good lists put out on Twitter and other social media where they literally, it's a Google sheet of all of the various fellowships that are available. And actually quite a bit more than even I would have just naively assumed before doing the research. But I just think that the ability to highlight people whose ideas are really interesting, but for a variety of reasons, they can't get funding for them or they have other obligations, which is often the case. This was an opportunity for us to do that. And so far we've only had one class, but some really great things have happened. I was just on, for example, yesterday a call with an Indian fellow who we gave a grant to, and he made a music video with it. And I really didn't know his backstory. What happened was it went hyper viral in India, and it's got tens of millions of views. And he's being courted by all of the major labels by all of the major companies, etc. And It was just great to hear from him, his journey and his experience. He's got a bit of Siddhartha in him, in that he meditated for a long, long time. If you know the story of Siddhartha, he's who became Buddha. And he just had this fascinating story and it was just so lovely to see our little grant. Really, it was a grant, which are $10,000, not the $100,000, that made a big difference in his life. And so that's what we're doing and we're just loving watching the results.

Tom Morgan: So sharp-eared listeners will have noticed my five-year-old jumping into the room during this because Jim and I are recording during the weekend. So I refuse to edit that out as a concession to my real life, although I'll remember to lock the door next time.

There's like 15 different areas I want to drill into here, but the one that feels most important to me is tell me what your life has been like in the last 12 months since you've started doing this, qualitatively.

Jim O'Shaughnessy: Oh, it's been fabulous. You know, it's the one problem that I'm facing is I don't scale as an individual. Luckily, I have a fantastic group of teammates that make all of this possible. You know, it's funny because other people's ideas about how these fellowships get awarded, many of them think it's just like me. It is not just me.

We have a full team going through them and they get up to me after the team has vetted them and interviewed them and all of that. But my life, literally Tom, has been just, it's been one of the best years of my life. Getting a chance to meet and learn all of the stories of a widely and wildly disparate group of people. I mean, if you looked at an average day, I could start the day having a Zoom with somebody who is a filmmaker and has got a great idea for a documentary that happened this week, for example. And then you shift to a meeting with our venture team and you get pitched on some of the most incredible ideas that people are starting companies around. I think it's an amazing time to be alive in that sector as well. But then reading the finished copy of one of my editors at Infinite Books got done with a forthcoming title and just watching all the changes and chatting with him and listening to why this changed, not that changed. So just an infinite variety, but all incredibly fulfilling.

Tom Morgan: See, this is why I want to drill into this idea, because for the last few months I've been exploring the concept of donations and why wealthy people give their money away and for what reasons. And knowing people on both sides of that dynamic, it's been very interesting to me that in the relationships that maybe don't go as well as they should be going, what happens is, is that the donors often get right up to the edge of giving money to something. And then it progressively gets less and less open-ended and there are more and more strings attached and the amount of money gets smaller and smaller and smaller. And a lot of people just often start out with a very narrow vision that this is the thing I want to accomplish and this is how I'm going to go about it. And whilst I don't think there's anything intrinsically wrong with that very focused attitude, I look at what you've done and you've inverted it and you've basically said to the world, bring me the most interesting people, by saying that you don't have that many strings. And it strikes me that the benefits for you in your life have been very, very tangible relative to someone that has very tightly prescribed goals. And do you have a, I mean, you probably know vastly more wealthy people than I do. Do you have an idea why people behave that way and what stops them from being patrons in the mold that you've become?

Jim O'Shaughnessy: Wow. Well, first off, let me just say, I wouldn't criticize anyone who was giving their money away for whatever reason that they have for doing it. I mean, if you know the history of philanthropy in the United States in particular, we did not have a tradition of a government supporting the arts or governments building beautiful museums or a variety of other things. And so, you know, the robber barons were not the greatest people in the world. But one of the things that they did, which really did start out the trend in the United States of philanthropic activities was give away a lot of money. I mean, look at Andrew Carnegie. I mean, there's a reason why there's a library in virtually every city in America, and that's due directly to Andrew Carnegie. So there would be a good example of he had a very specific, narrow idea about what he wanted to do. And yet the good that came out of that, I think is difficult to calculate, right? But in my instance, I just, I'm insatiably curious. And when I found myself in a position where I could act on that, through these fellowships and these grants, I felt, well, I want the biggest funnel possible. And the only way you're going to get a funnel of that size is literally to say, no strings. And, you know, now, does that open you to quite a few wacky ideas? Yes, it does. But you know, guess what? Some of those wacky ideas we're going to fund because they might feel wacky to committees and whatnot, but they're really not at all. One of the problems that I see with, I had Rupert Sheldrake on the podcast recently and he's a brilliant, brilliant scientist, but had the bad taste to turn on his colleagues after, I think one of the reasons why he got such draconian treatment was because he was the poster child for the establishment and the citadel of science. He took the top honors at Cambridge in biology. He was a special scholar at Harvard. I mean, literally, he was Mr. Inside. And then he went and published a book that was deemed heretical by the editor of Nature magazine, Sir John Maddox, at the time in 1981, and literally said, “this is a book for burning.” I love smart people with ideas like that because if you look at history, most heretics literally had to give their life. They ended up being burned at the stake or beheaded or any, they certainly had lots of novel ways to kill people back then.

But nowadays, hopefully, they're not giving up their lives, but they're getting excluded by institutionalized grants and things like that. If you look at what's getting funded in science, it's generally speaking not anything that's going to be a true paradigm shift. So one of the things that we try to do in our tiny way is to take those people seriously.

Tom Morgan: Yeah. I was hoping to wait more than 20 minutes before I took you to crazy town, but I can't not do this now. I listened to your podcast with Sheldrake because I'm mega fans of you both. And then later in the week, I encountered an article by Daniel Pinchbeck that made reference to Sheldrake's theory in a way that I've never thought of before. He talks about what he calls radical occultism as a worldview, where he talks about how a couple of hundred years ago, Westerners would go to Tibet and they would see a monk leap so far it was like they were flying. And when we hear accounts like that now, we just assume that everyone lost their mind, right? Or it's just some sort of creative license. And then he's like, actually, no. If you think about it in terms of Sheldrake's morphogenetic field,

For people that aren't familiar with the idea, it's essentially that reality has a real solidity and inertia to it, but those habits are... Well, sorry, the tendency of reality is kind of like a habit, and if enough people believe something, it then starts to change the nature of reality. And the implication of that idea is that our worldviews increasingly shape our reality, and you don't have to believe any of the things I've just said to know that that bit's true.

But his argument is essentially that as the world has become more closed down and rationalistic, magic has withdrawn from the world as even a possibility. And the thing that comes out of that idea that I find just staggeringly optimistic is that that negative downward spiral also works as an upward spiral. That if people suddenly believe that our reality is somewhat malleable (and we can tell what you're trying to do in terms of your media arm), you can tell stories that are both optimistic and true. You can create this incredibly virtuous cycle where people start to believe that world is possible and then that world starts to get created. Does any of that kind of mesh with you? I know it's a bit bonkers.

Jim O'Shaughnessy: I actually don't think that that thesis is bonkers at all. It seems pretty self-evident to me. I think that, you know, the idea of Robert Anton Wilson and Timothy Leary called them reality tunnels. I saw Adam Grant, who's written some great books on how to rethink things, called them reality or actually quoted somebody calling them reality goggles. The idea that we create our own sense of reality, our own version of reality, is relatively non -controversial, given much of the recent research that we're able to look at empirically. I put up two quotes every day, I call them two thoughts, we're actually doing a book on it with those two thoughts.

But one of them, I can't remember whose quote it was, was that if you want to destroy a country, destroy their stories, because they will tell pessimistic, downward spiraling stories about their prospects, about their history, about everything. And so I don't look at it in the least bit controversial to say that you know, you become what you focus on. What you continually focus on becomes your reality. I did a thread on Twitter called “the Thinker and the Prover.” And I tend to try to look for very pragmatic, practical uses of these ideas. And so I don't know about the monks who are leaping across, you know, like matrix -like. But one of the things that I do believe, passionately believe, that if you continually tell yourself that the world is a horrible place, guess what? The world you're gonna experience is gonna be a horrible place. It will find you. And conversely, by the way, let me hasten to say, this doesn't mean that you can sit on your couch and say, I'm a millionaire, I'm a millionaire, I'm a millionaire, and become one. I think that you've got to do the work. You always have to do the work. You can talk and tell your boy, Jung, say: “you are not what you say you will do, you are what you do.” And so I believe that we know so little about the nature of reality, the true nature of reality. That's why, for example, I'm not a religious person, but I'm not an atheist and I'm not an atheist because that requires as much, if not more, belief, I think, than being open to all sorts of different models as to what the true nature of reality is. And so I just, I'm endlessly curious and try to see things like Dr. Sheldrake. We in fact are looking at working with him on creating an app for determining whether you can increase your intuition. But my version of that is very nice because it aligns quite nicely with Dr. Sheldrake's. I'd love to see if it's true or false under scientific conditions. It's, let's test it. Let's see if that can happen. And I was on another Zoom with him and I said, you of course would publish even if it was a no result, right? He was like, “of course!” And then, you know, he listed all of the things. In fact, he'd listed something he had just published where his thesis did not prove to be correct. So I think that what you often see these days is people trying to shut down the question part, which is really crazy to me. We should be willing to entertain a broad array of questions.

But then we should try to be pragmatic about it and we should say, well, let's take a look. Let's see if this actually is helpful or not. So yeah, that's kind of the way I look at it.

Tom Morgan: One of the lines that stood out from Sheldrake in that interview was essentially that he named, I think, the BR Institution in Portugal. That's the number one psychic research lab that I think it gives away about a million bucks a year. And the Large Hadron Collider is the second one's being built for 20 billion euros. And you're just like, you know, we can do both. But like the idea that there's no funding whatsoever in these areas that may actually bear serious fruit. And the fruit I think would be that if our reality is more negotiable and malleable than we think, we have slightly more freedom to follow our bliss, knowing that there'll be positive feedback from our environment. And that for me strikes me as sort of the lowest hanging fruit that we can get people to consider practically, which is that if you think that the universe will respond beneficially to you pursuing your passions, that lowers the bar for people to do it.

And I think that plays into one of the other most interesting things that you're doing, perhaps not coincidentally, which is the fellowships. At the moment, if you have a fascinating idea, it's just impossible to get that funded. But I know that you can't fund everyone. UBI remains controversial because some people would just be lazy with it. So I think I know 10 people individually, and I know we have mutual friends, but I know 10 people individually that have applied for your fellowships.

When you're looking at these, what stands out to you in terms of things that you get excited about?

Jim O'Shaughnessy: So we get very excited about things that, as you yourself just said, are very intriguing, but are ideas that the citadel of science, if we're talking about science, or any other institutional type funding would be absolutely a no on. Now, that doesn't mean we're out searching for what others might call crackpot ideas. But we are absolutely open to a compelling thesis where the person has demonstrated proof of work for the most part. These are things that have really drawn their obsession or attention for quite a while. And that seems like a reasonable thesis to explore.

So, one of the, you know, another favorite of mine, as you well know, and I'm going to get you to read all of his books at some point, but it's David Deutsch. And one of his quotes is, “if it does not violate the currently understood rules of physics, it's true.” And I've always loved that line of his because it's a, it's a, like, spoken almost like a true heretic.

If you were looking at institutional science, et cetera, my God, you'd think that that would be the one area of human history and of life where the general rules of human OS don't apply, but they do. I mean, look at the way the Citadel treated Dr. Sheldrake. Look at the way it treated David Bohm, whose implicate and explicate order ended up being through testing, proven, right? And if you look at the way Oppenheimer tried to suppress David Bohm's work, it was because of politics, because he was apparently briefly a member of the Communist Party. And when you like, if you look at it, it's like the movie Mean Girls, right? You've got the correspondence between Oppenheimer and his fellow scientists basically saying “we must ignore David Bohm's work.” If we can't disprove it, we must ignore it. And you're kind of looking at it like that's insane. And yet it, throughout the history of most of the greatest innovations, what you can almost always count on is a very healthy chorus or Confederacy of Dunces, as the quote goes, who will oppose it, scream it down, say it's wrong.

And that you know, that's the precautionary principle run amok. If you are so fixed and dogmatic in the way you look at the world, you create stasis. And in my opinion, stasis is death. And we want movement, we want life. And so therefore anything that we can do to advance ideas that are out of the mainstream, but should have a fair hearing, as it were. We're gonna get very intrigued by that. And then also another, it doesn't have to be just science. So for example, we funded last year and the documentary will be coming out, I hope soon this year, but a young man whose father, after the communist revolution in mainland China literally swam to Hong Kong. He swam to freedom. And when we were interviewing the young man, I learned I didn't know anything about this. And you know, I go down a lot of rabbit holes as you know, Tom, and I'm like, what? And so he gave me the whole history: thousands of mostly men, but some women, after the takeover by the communists in mainland China swam to freedom in Hong Kong. And so that really grabbed me as, wow, what a story. I didn't know about it. That's a story that needs to be told. But why was he doing it? He was doing it for a reason that just, you know, that he got me when he told me the reason he was doing it. He was doing it because he wanted to know his father better. And his father was one of these buttoned up, closed-off type people who wouldn't talk about this experience with his son, with other family members, et cetera. And so he realized the only way that he was gonna get his dad to do it was to make a movie about it. And so things like that we find also really, really interesting and really important because there's a lot of stories that aren't being told, that we think should be told.

Tom Morgan: On the science thing, I was introduced to a lovely woman called Mona Sobhani about this time last year. And she's a highly-credentialed neuroscientist that had a series of encounters that led her to exploring psychic phenomena and writing a very good book about it. And I then read four or five books last year, which basically said that the statistical evidence in favor of these things is dramatically higher than you ever thought it would be and effectively proven. And, I don't actually, funny enough, I don't really have a dog in the fight in this. I haven't had that many experiences myself that I would categorize as “psi”, but it opened my mind to a possibility that ordinarily if someone told me they went to see a psychic, I'd just assume that they were a gullible moron. And now, and I've read lots of books about the techniques that charlatans used. So I just assumed that applied to everyone. But what was incredibly interesting to me over the course of the last 12 months is I've raised this as a topic of conversation with a lot of my friends and a lot of people I've met. And there has been a fairly tight one-to-one correlation between how rational and intellectualized someone is and how angry this topic makes them, like actually angry when you bring it up. And it made me think about the whole science and heresy angle that I've noticed that the one thing that really triggers people at any kind of subject area that threatens the sovereignty of the intellect. The idea that there's any force outside you that might be guiding you, that there are any forces outside interacting with you in the environment, that there's a form of intelligence that might be a better guide than you for your future growth, any kind of intuition, stuff like that, gets immediately shouted down by the citadel, which in itself is super interesting. But the place that I think it's going is the incorporation of that kind of philosophy into a worldview, kicking and screaming.

And one thing that you've talked about a lot in public, and I'd like you to drill into a bit more, is your concept of the great reshuffle and what that means to you and how OSV is playing into it.

Jim O'Shaughnessy: So first, just to comment on the idea of those in power or the institutionalized power trying to suppress ideas that are against or somehow contrary to their own. I mean, that's as old as we have written history, right? For most of human history, the dynamic of the rulers versus the ruled, in any of the arts or sciences was very much a zero-sum, negative-sum in certain cases, game. And it's not just science, right? Impressionists got their name as a term of derision, not as a term of admiration. The French Academy of the Arts had grown very, very stale during the time when Impressionism was emerging. And they did everything possible to snuff it out. And the term Impressionist was meant to deride them. You know, oh, it's like a child finger painting. It's just an impression. And so some of the greatest artists of all time are, of course, of the Impressionists, but they were ruthlessly suppressed at the time, just like the early sciences ruthlessly were repressed, by usually the church. But then what happened was the science itself got kind of a church-like attitude and started descending into dogma, i .e. these are facts, in quotes, that you may not challenge. These are ultimate truths and if you question them in any way, you are guilty of heresy and you are an apostate and you must die, period, right? Again, back to Dr. Sheldrake, Sir Maddox made a comment on a BBC documentary in 1981 about Sheldrake in which he said, “I had exactly the same right as the Pope did when he told Galileo he was a heretic.” And I'm watching this and I'm thinking: “Well, first off, really bad example, because Galileo was right and the Pope was wrong. But dude, you are the editor of the most prominent scientific journal, Nature, and you are talking about your infallibility?” I mean, the heart and soul of true science, not scientism, but true science, it's like punk rock anarchy. Take no one's word for it. Say f*&k you, man, I'm not gonna take what you tell me is true. I'm gonna examine it, I'm gonna test it, I'm gonna see whether we can negate it. And that's the spirit that was starting to get suppressed. So those things and those notions are as old as the hills. I definitely think that a more whole-brained approach, a more inclusive worldview is only going to let you see things that you were blind to before. The other author that I'm always trying to get you to read is Robert Anton Wilson. He's got a great book. I can't remember the exact title, but it's about why were all of the early gods goddesses? And I think it's along the lines of Isis is returning and boy is she p!ssed is one of the titles of the book. And in it, he goes to great lengths to say, you know, when the men took over, they made short shrift of all of the earlier female gods and tried to replace them or negate them or Mary Magdalene suddenly became a prostitute, right, as opposed to many contemporary accounts of that time really kind of thinks you as Christ's wife. And so I'm all in favor of let's just, let's look into things. Let's see where they lay and let's try to be as open-minded as we can. Now, this doesn't mean that I believe that like, you know, I can teleport over to you in your Manhattan apartment. I would love it if I could. And I'm not saying that ultimately I might not be able to or some one of my descendants, but for now I can't do that. But what we really are all about with the fellowships is just: we are very open-minded to the spirit of inquiry. And if we've been too hyper rational in the past, then let's look on the other side of that coin.

Let's just bring that back. I don't believe that one is superior to the other. As you know, I'm a huge fan of Taoism, and at the heart of Taoism is the idea of Yin and Yang. And to say that we should only be Yang or we should only be Yin, I think is to completely not understand what they're describing, right? The idea of the Tao, especially the unnamed Tao, is that creation comes from the blending of the masculine energy, the female energy, and if you don't want to gender it, the rational versus the spontaneous and creative. There's all sorts of different ways, but I think sometimes the words themselves get in the way because when we label something, we negate it. I'm stealing that from Wittgenstein. And I think that's quite true. When we label something, we put lots of definitions on it. We give it a label and then we really stop thinking about it. And so I'm very much in favor of, you know, we need Athens and Sparta. We need, we need Plato and, you know, the, or sorry, we actually need Lao Tzu and Confucius to keep the comparison more valid. And so I'm very much enamored of a holistic approach that takes all of these viewpoints into consideration and not simply, you know, well, we're talking about Dr. Sheldrake, materialism has taken over much of science. In other words, if we can't touch it, if we can't negate it, if we can't do that, it doesn't exist. And I think that is an impoverished way of looking at the world. And when you have an impoverished lens, you see poverty.

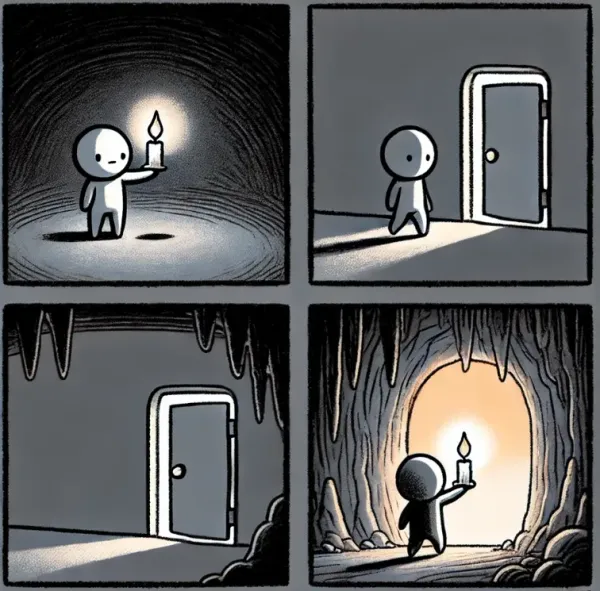

Tom Morgan: It's so funny all those things you just said because it's deeply resonant like one of the themes I've been writing about for the last year or so is this return of the archetypal feminine. And I stayed away from that framing for a long time because of the whole gendering of it could be seen as problematic and then you get into it and you just realize no we each have like a masculine and feminine side and that's just one way of characterizing it. But in the call to adventure it typically comes from the feminine side, you know what Carl Jung called the anima. And in the movies you see that as Trinity in the Matrix bringing Neo to the club or Princess Leia getting Luke Skywalker off Tatooine. But all that means in daily life is that when you're stuck in a rut, it's often your intuition and your passions that get you out of that rut and that question that you can't stop asking that gets you out of that rut. And I feel that our imbalance towards that masculine energy, that materialism is actually like hurting people on an individual level. And it's interesting to me that you're helping get some of those people over that barrier through actually providing them, you know, material support. But I do feel that the fact that we've absolutely obliterated the role of the intuitive in modern society and with it, the role of intuition, that really freaks me out, because it basically means that a lot of people get stuck in some very dark places because they don't have the faith to leap when they need to.

Jim O'Shaughnessy: Absolutely. And you know, it's funny you're bringing up Joseph (holds up a book by Joseph Campbell). Listen, what's really interesting to me about that and about Campbell and about Jung and Dr. Sheldrake's idea of the morphic field is they're all circling around similar things, right and and, let's stick with Campbell for a minute. How many of the top 10 grossing movies of all time have been Hero's Journeys? Do you know the answer?

Tom Morgan: I did this research a couple of years ago and it's 11 of the top 15.

Jim O'Shaughnessy: Yeah. So the vast majority, you use the term resonance. Listen, you want resonance, you want to see what people really resonate with. Just look at that. Look at the box office. If you want to be completely like, well, that doesn't make any sense. Well, if you want to make a lot of money, you might want to understand the hero's journey because it deeply resonates with the human experience, lived experience. And by the way, the movie I brought up, Rudy? Hero's journey, total hero's journey, right? He goes and tries to do the impossible, he loses the girl. I mean, like all of the steps of the hero's journey or Rick and Morty's story circle are present. In fact, one of the things that we are doing at O’Shaughnessy Ventures is we are generating all sorts of hero's journey stories via AI. And it's really interesting because the thing that fascinates me about AI is that it can look at an array of 100 million data points and say, oh, this, this, this, and this all connect.

Do you ever think about the synthesis of these four, of this hundred million data set series? Well, humans can't, AI can. And again, it looks and finds liminal spaces. And to me, that's fascinating. It's not replacing us, it's a tool which we can use to see those insights that we simply couldn't see otherwise. And you know, it's like I personally think Tom, this is maybe the most exciting time in human history to be alive. And everybody is like, well, not everybody. I don't want to be guilty of this myself. Many, many voices are pessimistic and filled with doom and filled with fear. And honestly, Good Lord! Study a little bit of history, man. And you would understand that you should thank whatever your gods are, that you are alive right now. I mean, simple things like every time I step into a hot shower, I say a silent thank you to the universe. Do you realize how few humans throughout history have had the ability to turn a knob and get hot water and have soap and be able to clean themselves? I mean, my God, it goes back to that's where Marx got the term the great unwashed. What he meant by that was: they didn't have soap. They couldn't clean themselves. Only rich people had soap. And you look at what, you know, free markets and free inquiry has given us, and it's this cornucopia of wonderful things. Now, has it also given us horrible things? Of course. But that's where error correction comes in. And that's where, you know, every, everything that, every advance that we make comes with problems.

We just have to hope that the problems are better problems than the ones that we had to deal with in the past. And the idea that we live in a world right now, especially we who have the luxury of living in the United States, where we still have, hopefully, the rule of law, we still have a first amendment to the constitution, which prevents the government from stifling what we can and can't say.

And by the way, if we didn't have the First Amendment in the United States, we'd have speech laws just like they have in Europe, just like they're putting in Canada right now. I mean, the founders, we have much to be thankful for and we really need to thank those guys and women because.. golly! But the point is the idea that we can move forward without friction or without problems, new problems being created is fanciful.

We just hope that we can always error correct along the way. And, you know, can you imagine fire? If you looked at some of the doomsayers today, if they were around when fire, they would be like, no, that's horrible. That's really, do you know how f*&king dangerous fire is? Well, of course it is. But after we invented fire, we invented fire alarms, fire extinguishers, fire departments, fire doors, fire warnings.

We didn't want to try to ban the tech of fire. We worked with it.

Tom Morgan: So I was thinking about this yesterday when I knew we were going to talk.

I found that there's two ubiquitous myths. There's the hero's journey. And in short, I think that the hero's journey is teaching you to be in alignment with the forces of evolution and all of the universe that can create through you. And the opposite of the hero's journey is the myth, which is “be careful what you wish for,” which is when you go to the witch and you say, “please give me this!” Aladdin gets his three wishes. And one of them is “make me handsome so that the princess will love me.” Or “make me rich so that the princess will love me.” He gets it and she finds him boastful and arrogant, right? You want something and it's not what the universe wants for you and things go horribly wrong. And we've been telling that story for hundreds of thousands of years. And my now dear friend, Kyla Scanlon, who I know is a fellow of yours, she was on stage with me a couple of weeks ago at a conference and she put up this slide from an article called “the limits of billionaire's imaginations are everyone's problem.” And effectively the argument was that the billionaire class no longer has imagination. And a lot of our future worldviews are actually either very kind of head-based or just linear extrapolations. So most people default to doomerism, which is a linear extrapolation of trends they don't like, or techno-utopianism, which everything is going to be okay once we just have more technology. It's very interesting to me that things go wrong when we act only with our head. That's “be careful what you wish for.” My head knows better than my heart. And our worldviews when they're driven by our head are also incredibly devoid of life. And we don't even take the heart seriously as a culture in terms of an organ of cognition. But what I've noticed is that whenever you have a heart -centered worldview, it's unexpected. It's often a little bit wacky.

But for me, it gets people much more galvanized and positive relative to the other options. And I think represents a meaningful pivot for our society. So it's not just AI will save us, but it's human-centric AI that will save us. It's things that can allow this new era of human flourishing. And it strikes me that there are very few people telling those kinds of stories in the public domain. I can count them on less than the fingers of one hand.

And that for me is really interesting and that I think we should all be working to elevate those kinds of heart-centered future stories.

Jim O'Shaughnessy: Well, as you know, Tom, from our numerous conversations, I don't like deterministic either-or thinking. I don't like zero to a hundred, black, white, yes, no. I think that we are deterministic thinkers living in a probabilistic universe. And generally speaking, either hilarity or tragedy ensue. So I think that I don't know what would be driving, you mentioned billionaires, I don't know that we should just simply look at them as the class who are being naughty or whatever, because a lot of largesse and giving and patronage is now done through government. And so you have the NIH giving hundreds of billions of dollars to what, in my opinion might be incrementalism, right? And so rather than say, you know, that's bad, which is my opinion, I think that, but let's be really careful. It's just my opinion. And one of the things that we humans often do is we often confuse our opinions with, you know, a God -given fact. And I don't do that. I know that probably all of my opinions, most of my opinions are wrong. All you have to do is study history. And if you and I, getting back to time travel or teleportation, if we could travel back in time, just let's, we don't even have to go that far back. Let's go back 500 years. And if we could know who were the dozen smartest people on the planet 500 years ago. And you and I were able to gather them all together, what we would find is how shocked we would be with everything they believed, because we would know being 500 years advanced from them that they were wrong. And so rather than either/or right/wrong, I prefer to think of it and life as movement, as directionally moving upward.

Now that doesn't mean that you don't have some sharp downs, right? We had the dark ages, they were not great. But the idea that we, life is about becoming, right? It's about growth, it's about movement. If you stop moving, if you stop growing, you start dying. And if you are dogmatic in your outlook, if you're closed-minded, if you think that what you happen to believe has a purchase on 100 % truth, you're brain dead, in my opinion. And so I think that it would be great if people who had the means, right, back to your billionaires who had the means started doing more patronage. I think patronage is, I mean, you look at the Medici, for example. There's a reason why all of those great artists found themselves in Florence. Florence was the city state that the Medici ruled. And so what happened? They were a beacon. They were a Schelling point, and they started giving all this patronage and what happens? Give the patronage and the artists appear. And so when you look at why Florence was so important in the Renaissance, it was because of the symbiotic relationship that existed between the Medici and the artists who they gave patronage to. The artists were drawn like moths through a flame. Because my God, I can actually have this idea of mine become a reality because of this family in Florence, well, that's where I'm gonna flock to. And so I think that, you know, even, I think if you gave me a little while with even the most self -centered, self -interested billionaire out there, I could reframe it for him or her and make it along the lines of: this is in your own best self-interest to do because like this will ultimately be better for you because you might be able to invest in it or take advantage of it. I mean, there's a million ways you can frame it to people who are just incredibly selfish in their actions. And you know, Adam Smith told us all about that, right? It is not to the benevolence of the baker that we owe our bread, but it's self -interest. And so if you really want it to frame it as not even being just a tiny bit altruistic, you can frame it along the lines of, hey, if you really just only care about yourself, Mr. or Mrs. Billionaire, you should be doing this because the results are gonna be amazing and fruitful.

Tom Morgan: It's one of the things I love about this though, which is that Cosimo de' Medici wasn't standing over Michelangelo's shoulder holding a chisel. He was just like, “go make something beautiful.” And then he was surrounded by beauty. And we're still talking about them now, but the stipulations weren't there. And I can say this about you because you probably can't say this about yourself, but I look at the last year of your life and what you've encountered. You've been flooded with abundance of interesting things by not having tightly prescripted answers as to what you want to find.

And I find that so interesting.

We're coming up on the last five minutes and the last time you met, you said something to me that I haven't stopped thinking about. It was this visual metaphor for a super saturated salt solution where basically if you drop one grain of salt, and if you're listening to this, I recommend going and check it out on YouTube because I've watched it now several times. If you drop one grain of salt into a super saturated salt solution. (And I'm now going to do it for my kid actually now that I've remembered, because we all know he's in the house). It suddenly crystallizes.

It's like that phase shift where it suddenly all crystallizes into salt. And you made the assertion that you think this is where we are. And this is where I think we are too, at the cusp of a phase shift. So, you know, for the last couple of minutes, just paint me a picture of what you think that looks like. And I think if anyone's listening to it, how do you capitalize on that as an individual to make your life as exciting as yours has become?

Jim O'Shaughnessy: I think that the wonderful things happen when you find people who are passionate, obsessed, skilled, you fill in the adjective, and then let them be thus, right? I have no interest in micromanaging anyone on my team, much less anyone we give a fellowship or a grant to.

I'm, this is like spreading Johnny Appleseeds, I guess. You see, you throw the seeds out there, in this case, it's a funding through a grant or a fellowship, and then see what sprouts. And the key to that though, is you can't have a predetermined outcome that you want to see as the answer, right? Because, that isn't real patronage. You can hire somebody to create something exactly the way you want it. I think that one of the big problems in a lot of corporations is this idea of micromanaging creative people. I'm not running a kindergarten at O’Shaughnessy Ventures. You can work from anywhere in the world. And there's people who are, it triggers them. If you want to work in an office environment, by all means do so. That's great. It just hasn't been in my opinion, the way that I've seen my ability to get some of the most talented people in the world to join O'Shaughnessy Ventures is by not prescribing, is by not saying, you know, this is the rule book and you must follow it. Now, of course, do we have rules? Yeah, you can't break the law and all of those simple things. But to be overly prescriptive is to cut off their source of creativity. And that to me is self -defeating. Again, let's make no mistakes here. I'm a capitalist and I hope that great things will come out of our for -profit branches. And who knows, we might even fund a fellowship that turns into somebody coming back to us and saying, you know, all the work I was able to do with the fellowship, now I'm going to start this company. You want to invest, right? You just can't, by thinking that you know ahead of time, right, that what the outcome is going to be, directionally maybe short, but what you want to do is you want to allow as much room for the creative, for the iterative, for the surprise, if you will.

Because that's where all of the really cool kind of, you use the term phase shifting, quantum leaping, paradigm shifting. I want to be careful because if I use too many buzzwords, I'm going to suddenly be the king of LinkedIn and I don't want that to happen.

Tom Morgan: Jim, you're an inspiration to me and I'm hoping this has been an inspiration to others. Thank you so much and I hope to speak to you again soon.

Jim O'Shaughnessy: Thanks for having me.